A Little Bit Shattered

I am sitting in my car wearing a mask, making my way through a series of orange cones in a parking lot that previously housed the California State Fair. The last time my car touched these grounds, I ventured out for an evening of carnival rides, popcorn, farm exhibits, and live music. This was back, of course, when herds of people would gather in the name of cotton candy and ferris wheels, nary a mask in sight.

Last time I was here, I ate a corn dog. Oddly enough, it is 8:45am and a corn dog sounds pretty good right now.

A snake-like trail of orange traffic cones directs cars through a handful of “stations”—masked professionals sitting on folding chairs holding iPad-like devices. At the initial stop, I present my vaccine card to a young woman with impressive eyelashes who records my name and birthdate into her tablet.

“How are you doing today?” she asks in a bubbly, upbeat tone. Is she a nurse? A volunteer? What kind of qualifications do you need to work at a parking lot vaccine clinic?

She directs me forward, gesturing with her hand the general direction I need to drive until I get inside a covered warehouse. I know the drill. I did this three weeks ago.

At the next station, another woman greets me with crinkly eyes, smiling behind her mask.

“See that guy with the light saber? You’re going to pull into aisle four.”

I follow her finger to the young man waving me into a cone-outlined lane, using a flashlight. I pull up to the designated spot, put my car in park, and turn it off.

Two women meet me at the car door, and ask me to pass my vaccination card and ID through the window. I am asked all of the same questions I was asked last time.

Are you sick?

Have you ever tested positive for Covid?

Do you have any known allergies to vaccines?

Do you have blood clotting disorders?

Do you have derma fillers?

Are you pregnant or breastfeeding?

I answer every question, and with one last punch punch punch into her tablet, the woman peppering me with questions nods at the other woman, who is already rolling up the sleeve of my shirt.

She wipes alcohol over my skin and asks if I’m ready.

I nod yes, feel the sting, and within two seconds, it is over.

“You did it!” she tells me, excitedly, as if I’m a two-year-old who just went to the bathroom on the potty for the first time.

I roll my sleeve down. She whips out a marker and writes some kind of code on my windshield, waving me through the exit with a simple, “Have a great day!”

I slowly drive out of the warehouse, and into the waiting zone where I need to be monitored for the next 15 minutes. I put my car in park again, and look around at the other dozen cars in the lanes next to me. I wonder about the people in these cars: who they are, what they do for a living, what the past year has been like for them. I marvel at how easy this was, driving through a parking lot, never once getting out of my car, being injected with a vaccine where I used to eat corn dogs.

What did it take to pull this off? How did we do it so fast?

In a state of emergency, the red tape and bureaucracy just … went away. It makes you wonder, doesn’t it? What else could we do? Who else could we help? What would happen if we started serving hot meals, passing out bottles of water and clean socks and medicine and therapy to those who need it most? What would happen if we harnessed our collective energy and resources toward morphing theme parks into triage centers more often?

***

I thought I’d be delighted to hear that vaccinated people don’t have to wear masks anymore, ecstatic I can wear lipgloss again.

But instead of feeling delighted, I feel cynical. We’re supposed to use ... the honor code? After this past year? After all the conspiracy theories, the insurrection, the fake news, the contested election, QAnon? We’re just supposed to … trust our fellow Americans?

A few months ago, when the mask mandate was still 100% in effect, I went to the mall to return a dress I had ordered online that didn’t fit quite right. I walked in among a handful of other people, including a man not wearing a mask. He was tan, and muscular, wearing a bright blue tank top. For the sake of the story, I’ll call him Chad.

A pretty twenty-something stood at the entrance of Nordstrom, holding a tray of masks in one hand and a plastic tong in the other, like a cater-waiter serving hor devours at a wedding.

Upon spotting Chad, she kindly said, “Sir, you need to wear a mask to enter the mall.”

Without flinching, he threw his hand up in her face, said, “No thanks, I’m good,” and kept walking.

I could tell she was caught off guard, as were others watching this scene unfold, but she kept her composure and said it again, this time more sternly: “Sir, you cannot come into the store without a mask.”

At this point, Chad was already past her. He whipped his head around with an arrogant smirk and repeated his line, “No thanks, I’m good.”

And just like that, he disappeared into the rest of the shoppers, breathing his germs and privilege all over the mall.

I couldn’t believe what I had just witnessed. The audacity. The smugness. I thought of my friend’s immunocompromised daughter, who has already spent part of her life in the ICU. I thought of my other friend fighting cancer, the eight-year-old child in Everett’s class battling leukemia, my own grandparents in their eighties. I thought of the recent data showing how racial and ethnic minority groups are being disproportionately affected by Covid.

Half a million people have died in the United States alone. And there goes Chad into the mall, pretension all over his maskless face, en route to Lululemon for more tanks.

We’re supposed to abide by the honor code with that guy?

I am not a cynic by nature. I pass out the benefit of the doubt like sticks of gum. Do you know how many times I’ve left my laptop on a table at Starbucks while I use the restroom? How many times I’ve asked—and trusted—a complete stranger to keep an eye on my things?

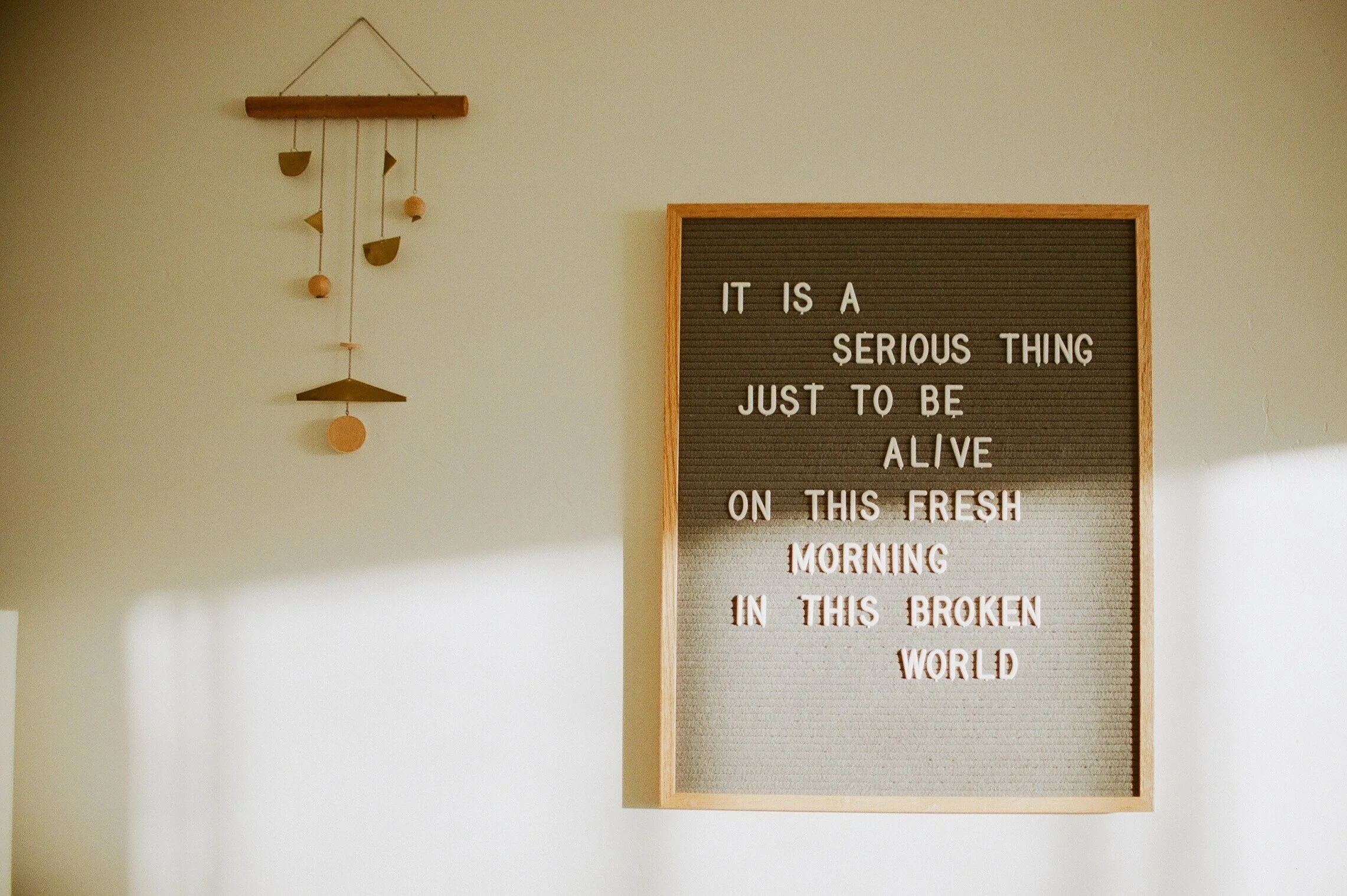

I keep thinking I am coming out of this pandemic okay. And I am okay. My family is healthy. My husband and I still have our jobs. I am abundantly grateful. But the day the mask mandate changed, hinging on the honor code, I thought of Chad and I thought of the election and I thought of white nationalists storming the Capitol and I realized, maybe I’m not as okay as I thought. Maybe I’m coming out of this pandemic a little bit shattered inside.

***

I drive straight from the vaccine clinic to the grocery store because we are out of bananas and milk and basically everything, and I want to shop before my arm starts to hurt.

Right outside the entrance of Trader Joe’s is a wooden stand holding a variety of herbs. Without giving it much thought, I grab four—basil, mint, rosemary, oregano. Inside the store I put cheese and burritos in my cart, ice cream and butter. I get peonies, too, as a post-vaccine present to myself.

At the checkout stand, an old lady gets in line behind me. For the sake of the story, I’ll call her Agnes. I smile at her from behind my mask, noticing a sparkly barrette clipped in her white hair. It’s gold and glittery, like something you’d wear to the prom. But we’re not at the prom, we’re at the grocery store on a random weekday, and she’s paired this accessory with black cropped pants, a teal hoodie, a pink tie dye mask, and sneakers.

Agnes—who, by my best calculation, is 80-something years old—recognizes the cashier swiping my food across the counter. They start chatting like old friends, and it becomes clear to me this is a routine of sorts. She must shop here often, maybe on the same day each week, and always stands in this line.

I stay quiet while they catch up, watching Agnes readjust the yellow flowers in her own cart and wave her hands around telling a story of how she recently got stuck at the airport. She laughs loudly through her mask, overjoyed to be standing in this grocery store on a sunny Wednesday morning with a gaudy clip in her hair. If she is cynical at anything or anyone, it does not show.

She seems delighted to be alive.

***

Back in the car, Kings Kaleidoscope comes on the radio:

Oh it's gonna be ok, with a little bit of faith

Oh it's gonna be ok, with a little bit of grace

It’s a catchy tune that gets stuck in my head for the rest of the day. At home, I unload the groceries and put the peonies in water. I line up the herbs on the kitchen counter, vowing to plant them later.

When later comes, though, I start to feel sick. With a sore arm and pounding headache, I climb into bed at 2 o’clock in the afternoon and stay there till dinner watching reruns of Dawson’s Creek, my comfort show du jour. I fall in and out of sleep, waking up just in time to hear Pacey Whitter say, “It’s life’s little twists and turns and bumps and bruises that make you who you are.”

For the next 48 hours, I am useless. Fatigued, nauseous, generally spent. Work piles up in my inbox, dishes pile up in the sink. I feel terrible, and I feel guilty for feeling terrible, knowing I’ve left my husband to take care of the kids on a workday while I remain curled up under my weighted blanket watching a love triangle unravel between Joey and Pacey and Dawson.

At one point my daughter wanders in and asks to nurse.

“Mommy, can I nurse you?”

She always says the pronouns backwards. A tiny piece of me hopes she never learns to say them the right way.

“Not right now, babe,” I croak, “Mommy doesn’t feel good. I’m a little bit sick.”

She studies my face, absorbing the scene of her mother lying in bed in the middle of the day.

“Be right back, Mommy!” she says, running out of the room.

A minute later she reappears at my bedside holding a blanket.

“Here you go, Mommy,” she grunts, lifting the blanket up to the bed.

The gesture is so sweet, so impressively intuitive for a toddler, I almost cry. I’ve barely thanked her when she disappears again, this time coming back with a wicker garbage basket filled with stuffed animals. I can’t help but wonder where all the garbage has gone. One by one, she places them on top of the bed next to me, naming each offering.

Here’s Elmo.

Bunny.

Uni kitty.

Mickey.

Lion.

Paw patrol.

Teddy bear.

I’ve never felt so loved in all my life.

***

It takes a full 72 hours for me to feel like myself again. As soon as I do, I venture into the backyard to plant the herbs I bought at the grocery store. Presley “helps” by moving shovels full of dirt from one side of the garden bed to the other.

I dig four holes, burying my feelings about Chad in the bottom of each one. I transplant the herbs, using my hands to pat the soil around each new plant, each new promise. This is my favorite place to practice stubborn hope: in the dirt.

Breathing in the scent of fresh basil, I marvel again at the life-saving vaccine I’ve just received in a place where I used to eat corn dogs. I think of the plethora of miracles and disappointments I’ve witnessed over the past year, the emotional roller coaster we’ve all been on. I think of my kids, who have been wearing masks for over a year to school and birthday parties and church without ever once complaining. I think of the vast humanitarian crises happening all over the world—the wars and famine and sex trafficking and lack of clean drinking water—and how only in America could we turn something as simple as fabric stretched over our faces into something to fight over.

I think of Agnes in Trader Joe’s, with her snow white hair and sparkly barrette and tie-dye mask. If I make it to my eighties someday, I hope to be like her: friendly with the cashier I see every week, rocking a jazzy clip in my hair, joy radiating out of my face because I’m delighted to be alive.

“Mommy can I hold you?” my daughter asks, her face smushed up against my knees.

I rip the gardening gloves off my hands and reach down to pull my daughter into my arms, humming the tune stuck in my head.

Oh it's gonna be ok, with a little bit of faith

Oh it's gonna be ok, with a little bit of grace